Julie Zhu "The Sound of drawing"

- Corentin Marillier

- 8 janv. 2023

- 11 min de lecture

Julie Zhu (1990*) is an American artist, composer and carillonneur based in San Francisco.

Through her practice as a visual artist and composer, Julie traces a very personal trajectory and her work explores the links between performance, music and the act of drawing.

I met Julie in 2020 during the Voix Nouvelles Academy in Royaumont and we have since worked together, in particular with Semblance, which will create a new work during the Royaumont Festival 2023.

You often say that you started by studying visual art before composition and that it is still an important part of your work. Can you tell me how it started ?

One of the first things I drew, and I still remember it, was my family's couch, whose wrinkles and large cushions reminded me of a huge, sick dog. My mother, who painted herself, always encouraged me to draw and it seemed very intuitive to me. I felt like all I had to do was print what I saw and put it on paper. I drew all through my childhood, and then I started painting. I was fortunate to have met teachers who really helped me develop my path as an artist. It has always been one of my great loves.

Did you follow a special curriculum in school ?

From my childhood to my teenage years, I was always practicing after school because it wasn't until college that I was able to take a double major, specializing in math and visual arts. It was wonderful and it really changed the way I approached art. Until then I was painting mostly in a very representational style and suddenly I discovered abstraction, minimalism and all the theory around it...

It was also during this period that I discovered the carillon completely by chance. I happened to have played the piano from the time I was five until I was fifteen and I always listened to a lot of classical music. At Yale, the carillon was located in a secret, almost anonymous location at the top of a large tower in the middle of the campus. No one had access to it. I heard about an open house where they were showing the carillon, but the stipulation was that if you went to the open house, you were automatically signed up for a few lessons. I took my lessons and fell in love with the carillon, and it became my instrument.

You play the carillon all over the world, you are invited in conferences, what does this specificity inspire you in your job as a musician?

I don't want to be wrong in saying this, but I have the impression that the world of carillon is an expanding microcosmos. What I am sure of is that there are more and more carillons in the United States and a growing interest especially from young people, contrary to what I have observed in France where many carillons fall into oblivion.

It seemed normal and instinctive to start writing for my instrument: while playing, while interpreting other people's music, one spots a detail, an element on which one would like to concentrate.

I like this diversity within the repertoire that makes the carillon a public instrument. When you play, and you have the possibility that people hear you at least two kilometers away, it creates a completely different relationship between performer and audience than music that is played in a concert hall. From country to country, the musical heritage varies but it is always based around three genres: folk song, classical music and pop. What people want to hear most is the Beatles. In France, it's Edith Piaf (laughs). I like the fact that we have the opportunity to bring people together around a common heritage.

I always add a modern piece to my program: either one of my own compositions or a piece I've commissioned from a colleague or friend. And even if most of the repertoire is based on traditional harmony, more and more recent pieces are interested in timbral, spectral aspects, and this opens up many possibilities. I think for example that clusters have a potential that is still untapped as well as electro acoustic composition because many carillons are now equipped with speakers. If you add electronics, you can increase the size of the carillons, which are already massive by nature, tenfold.

How did the desire to write for other instruments come about ?

For several years, I happened to teach visual art at summer school in Alaska. It was an absolutely beautiful place that brought together a whole range of artistic practices: music, dance, visual arts... During the week, teachers and students would present some of their work. All this was very stimulating, especially since collaboration between different disciplines was encouraged.

The second time I participated, the dancer Laura Careless suggested that we work together. I played her a carillon piece that I had written for my final exam at the Royal Carillon School "Jef Denyn". She liked it very much and created a choreography based on my music. A friend and pianist, Robert Fleitz, attended the concert that night and a year later, while we were both living in New York, he asked me to write for a concert he was organizing around pieces for keyboard instruments other than the piano: harpsichord, celesta, clavichord.

I particularly remember the celesta piece where I tried to draw from popular culture, especially from television shows or songs that had used the celesta: The Velvet Underground’s Sunday Morning or Mr. Roger's Neighborhood (a children's show broadcast in the United States). We put a lot of humour into it, the idea being to trace the history of the instrument through musical elements that everyone knew. And between each of these little pieces, there was a little recorded interlude of Robert breaking the fourth wall. I had wanted to add a performative dimension to the music, something I had already included in my work as a visual artist: Robert had his back to the audience, and I remember that tattoos were handed out to the audience that represented the score. This is kind of the entry point where I thought I could try to mix music and performance.

Let's talk about an important part of your work which is focussing on the relationship between music and visual art. When and why did you feel the desire to combine your two practices ?

One of the reasons why I continued to compose is very strongly linked to what I was experiencing as a visual artist. I was quite dissatisfied with how little time people spend on a painting: when you go to a museum, how many people browse from one painting to another without really looking at it? When we look at a painting, we give it a single second to grab us. I truly believe that if someone were to sit in front of a painting for the duration of a symphony, they would also be moved in the same way and with the same intensity. Not many people take that time, and that's why I like « traps » like a concert hall. The concert forces you to stay, you are forced to confront this music, according to social conventions that prevent you from leaving. You have to stay there even if you don't like the music and you have to confront yourself and I think that's a great thing!

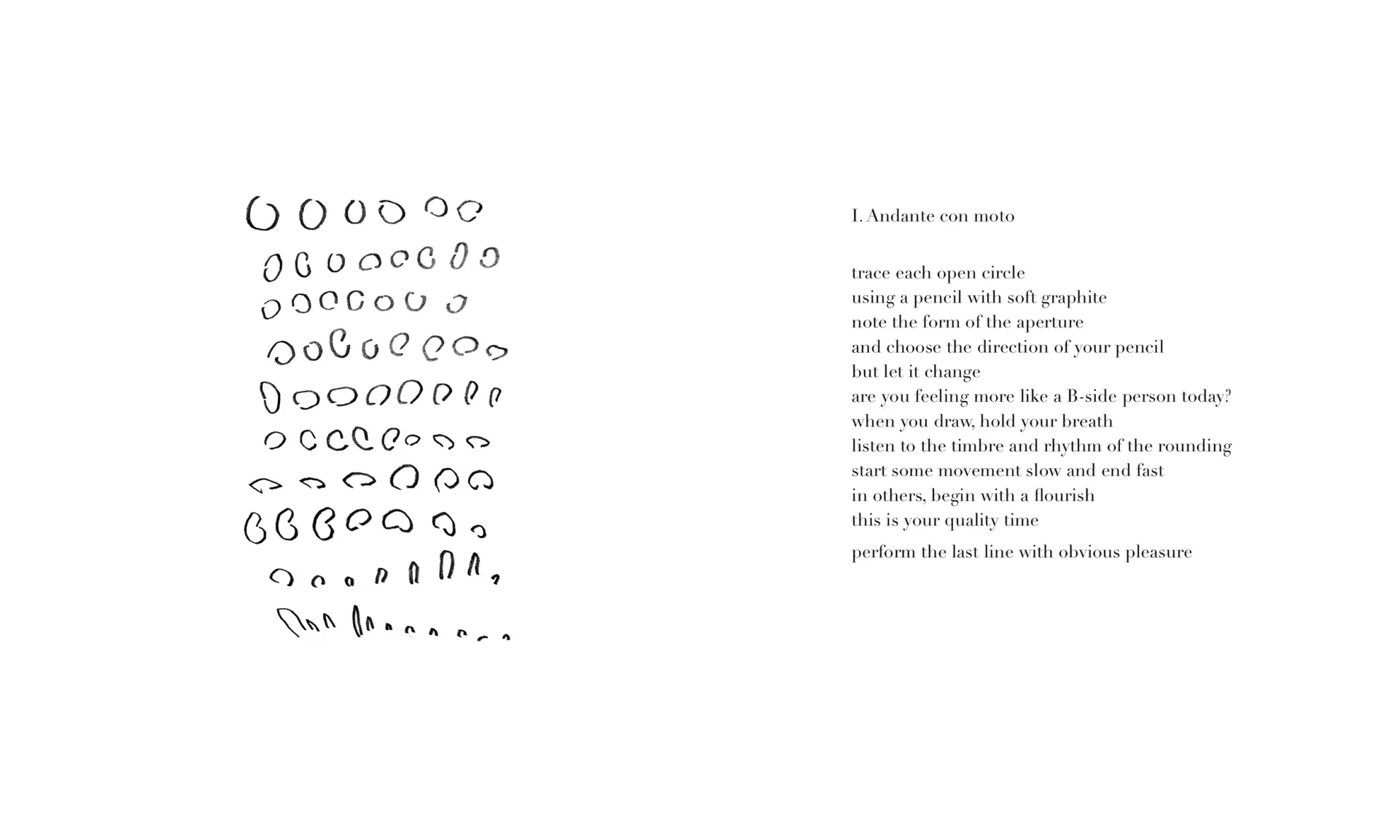

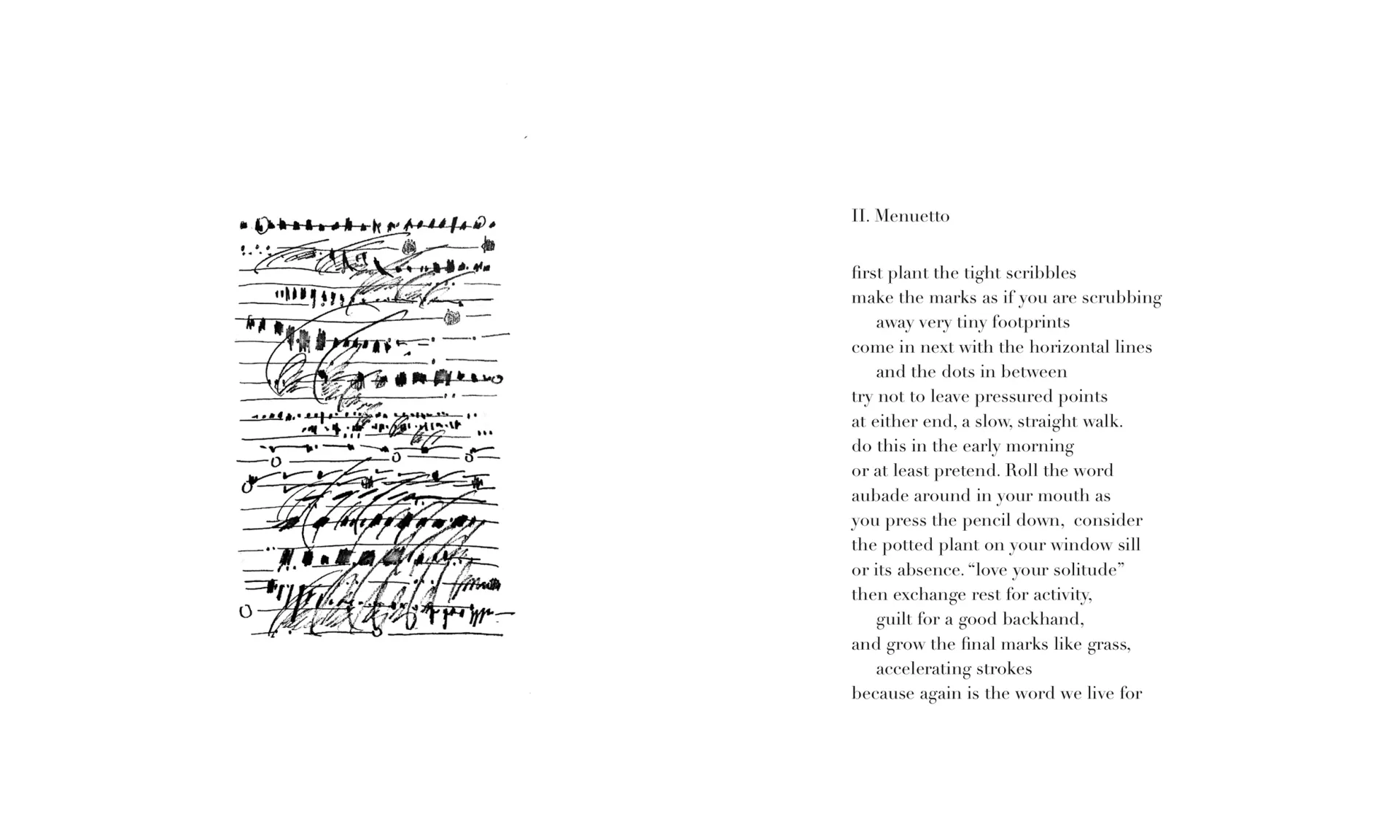

It was mainly because of these issues that I wanted to combine visual art and music, I wanted to find a way to keep the audience's attention both sonically and visually. So I started working with graphic scores, and one of my first projects "Accordion Books" was the result. Over the years, I have kept moving away from or returning to graphic scores, I don't think I have yet solved the equation between notation and graphics.

Which is to say ?

This is a very personal opinion but when I compose/draw a graphic score, I think that in the end, no matter what is on it, the result will always depend on who is interpreting the drawing, their background, what that person has played in their life. I'm sure that a John Cage piece or a picture of a tree could give the same result.

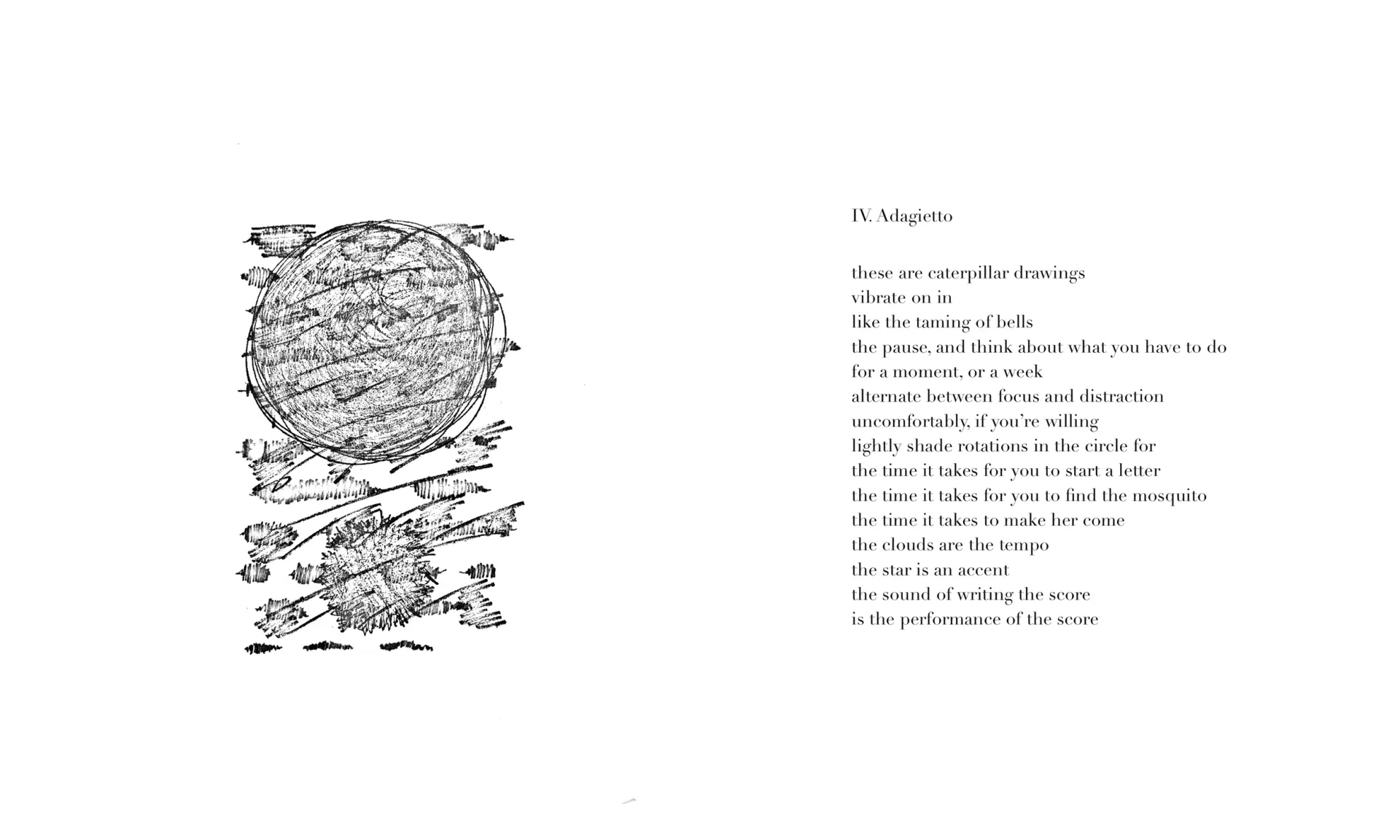

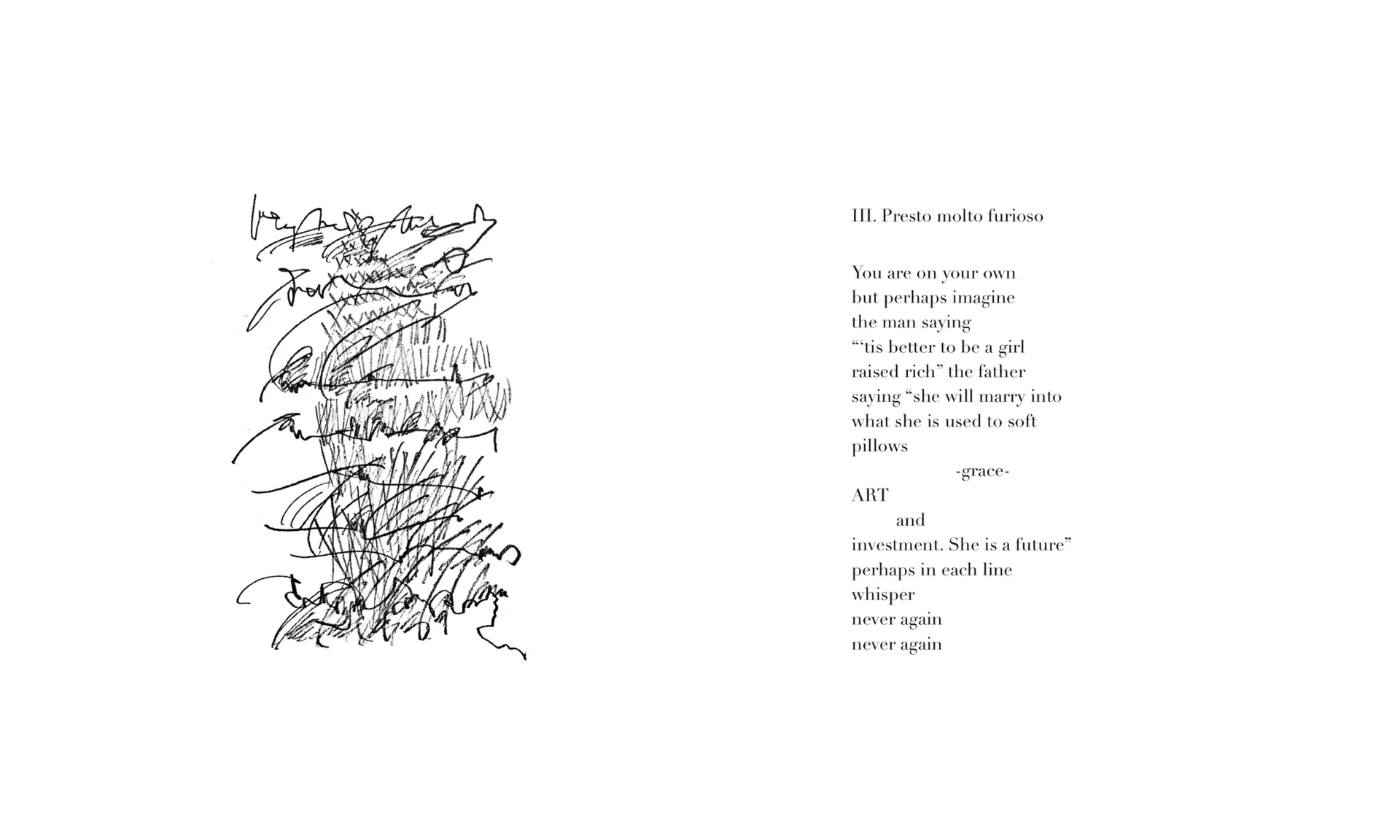

So I looked for a more specific connection between these two mediums. As I began to listen to the sound of what I was drawing, I realized that it was so interesting, so rhythmic, and that depending on what one is drawing, it evokes completely different emotions! Abstractions arise. When we write for example the sentence "I love you", we can already feel the delicacy of the sound of our pencil on the paper. And if you write "I hate you" you can also feel a certain strength. It would be difficult to really hear a difference because the "I" and the "you" are common to both sentences, "hate" and "love" have exactly the same number of letters. So you probably can't feel or perceive the difference and it's exactly this ambiguity and intimacy that I like to explore.

One of the first pieces written for other instruments that addresses this problematic is the piece "Write hand" for percussion and cello composed in 2017.

The piece was inspired by a poem by Ren Hang (Chinese poet born in 1987 and tragically passed away in 2017) that I translated and that the percussionist must write while playing three instruments of his choice. The piece was commissioned by the percussionist Tyler Cunningham and for this reason, I wanted percussion to be the main musical element, which is never very common: in a duet or in any chamber music piece, percussion is often there to punctuate, to give a breath. I was interested in this question of rhythm when writing, so what could be more natural than to entrust this task to someone who in essence understands the beauty of rhythm.

Next comes the piece "Toccata" for three percussionists who play several instruments while drawing on three large canvases in front of them.

For "Toccata", the challenge was to start from a rhythm and transcribe it into a drawing, whereas for "Write Hand" the writing of the text had served as a rhythmic matrix.

I had noted specific rhythms for the drawing and indicated exactly the position where the percussionists would draw. The score combined traditional western notation with graphic notation. I tried to give the same importance to the sound as to the visual by trying to focus on the sound potential of the writing, rather than the visual result. However, I wanted the drawing to be as beautiful as the sound and to create a beautiful abstract work. I thought I could do it, because I had enough tips to guide the percussionists, while they kept saying they couldn't draw.

This work helped me to push the relationship between gesture and sound and my last piece "Box", composed during my composition course at IRCAM, was completely in line with this research. The device was necessarily much more ambitious: the performer, Olivia Martin, was in a giant box where several microphones were placed and the sound device could reflect the path of her pencil inside the box. I also experimented a lot with frequency filters. For "Toccata", it was simply contact microphones with a very basic use.

In "Toccata" we witness both a sound and visual performance. If the music exists only in the present time, the canvases on which the percussionists draw exist as a visual work, what is your view on this antinomy ?

I think that these large boards on which the percussionists draw are a much more abstract, poetic and conceptual means of documentation than a video recording. I had indicated at the end of the score that the musicians could send me photos of the result and that I could imagine a personalized suite. I have always dreamed of bringing together all the paintings from each performance and using them to create another work of art in its own right, but for obvious logistical reasons, this was never possible.

You use the expression "sound of drawing" several times in your texts or scores. How would you define it ?

I tried to answer that with the series of pieces I mentioned earlier, "scribber scores" published in Ginger Zine. It's an inner dialogue, something abstract where we express our thoughts on paper. A performance for oneself and played by oneself. Because of computers we lose this relationship with paper. And in saying this, it is not necessarily by nostalgia. With this piece I wanted to explore a new level of intimacy.

Moreover, I have had another project in mind for a long time that I dream of realizing: I wanted to install and build a cabin in which one and only one person can enter. This person is asked to write a postcard to a friend. The surface or the paper on which she or he writes is amplified, recorded and the sound is broadcasted live by loudspeakers outside the cabin where other people wait before entering. People who write are asked to provide their friend's email address so that the soundtrack of the written text can be sent to them, which they will discover before they read the postcard. I appreciate this level of intimacy and want to share it with others through my work.

You have just spent a year at IRCAM as part of the composition program. There are many debates and quarrels in France concerning the return of a neotonalism, and minimalism has been discredited for a long time. Your music frees itself from these debates and does not hesitate to draw as much from experimental music as from more tonal music: I am thinking in particular of your piece "Pinks" that you composed during the Académie Voix Nouvelles in Royaumont in 2020. How do you perceive this typically European debate ?

I don't think I'm the most qualified person to answer this question. One simple point I can give that everyone will agree with: there is such an history in Europe... And that is as much an opportunity as it is a heavy burden to carry.

Coming to composition relatively late in my life, I have somehow retained a certain innocence about the works of the past and the pieces that are considered masterpieces and have been analyzed by most students in Europe. I enjoyed and learned a lot from this year spent at IRCAM. This way of trying to touch the exactness, to be in contact with the excellence among students, professors, technicians... This excellence has been made possible by the history and the past. But I can also feel a constraint, and I think that this dimension exists less in America where in general the "know-how" is perhaps less important than the "idea". Movements like Fluxus or Minimalism showed this very well and they continue to influence a lot of creation today. Someone like Iannis Xenakis came to music very late in life and brought this extraordinary force, which has marked the history of music forever, thanks to his background as a mathematician and engineer.

When I started composing, I heard a lot of so-called new complexity music (a musical genre led by Brian Ferneyhough among others), which was very fashionable in New York at that time. I didn't feel comfortable and was very insecure, because at that time I didn't write complex rhythms, polyrhythms, extended techniques, etc. I tried to write in a way that would make me feel more comfortable. I still tried to learn this language but the most important thing is to find your own way and one of the people I have to thank the most is Jarek Kapuscinski. His music is very tonal, but he simply writes what he wants without imitating or copying anyone. From that point of view, Stanford was a great place to be because you are far from the center of the new music world. Everyone is incredibly supportive of experimentation; you feel that you can make bad music in the service of trying stuff out. When I participated in the Académie Voix Nouvelles de Royaumont, I was very surprised that my piece you mentioned was well received. I had really thought that everyone would find my piece too tonal and would not find any value in it. I was really touched by that.

You regularly publish reviews of records or concerts in various magazines. Is it possible to talk about music?

In any case, you have to try... It's nice to talk about music, it's to discover a lot of new things, to think about it in a more advanced way, to order our thoughts in order to make our criticism clear. By the way, I'm not sure if we can call them "critiques", I don't see myself as a critic. If there is one thing that the music world should seriously consider, it is how to exchange our ideas, our points of view in a constructive and inclusive way and talk about music in a spirit of community and open to the rest of the world. Writing is part of that openness and I think our world is already small and anonymous enough to have to shoot bullets at each other. Buying and playing a CD of contemporary music in your CD player is already a generous act, so I’ll never just write “ah yuck I hated it, this music is pointless"... (laughs). There is always something to learn.

Comments